What We’re Reading, by Doc Hall:

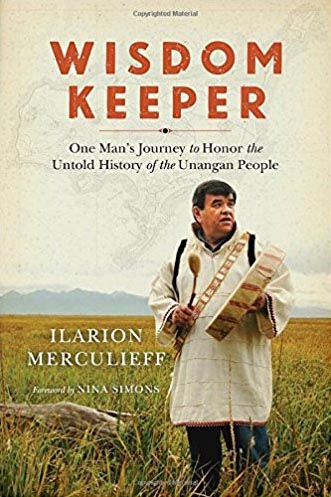

Wisdom Keeper: One Man’s Journey to Honor the Untold History of the Unangan People, by Ilarion “Larry” Merculieff

Merculieff is now Elder at Large of the Tribes of Alaska. From the age of 4 his tribe, the Unanagan, marked him for that position, but his personal journey to fulfill that promise took decades before he emerged as a leader and spokesperson for indigenous peoples all over the world. The book is an easy read. It’s the history of Alaskan Native Americans, the Unanagan in particular; plus his personal history. It’s unvarnished and unpretentious. Ilarion’s real humanity shines through.

Without reading his full story, few readers will grasp his message at the end: To fix our social, economic, and environmental problems, we must first fix ourselves. All our human conflicts arise from being disconnected from others and from all Creation.

Much of the wisdom of elders is from asking the right questions to resolve conflicts. He has examples. Some of his wisdom will seem familiar to readers into organizational excellence: Love who we are as flawed human beings. Don’t fight “evil.” Set examples for others to follow. Deal with our problems, issues, and processes, our priority should be our visions and dreams. What we focus on becomes our reality.

Emotionally, we have to sense our connection to all life. We may have different levels of technical understanding. However, a common feeling of connection bridges those gaps.

Seeing the history of Alaska from an Aleut perspective is a jolt. First, Merculieff is a Russian name. The Russians came first. Within two generations, 80% of the natives died of European diseases to which they had not immunity. The Russians enslaved the survivors catching and processing seals for the fur trade, but it was a losing business. In 1867 they were happy to unload Alaska on the Americans, who proceeded to use and abuse the Unangans for another 100 years.

Killing and processing seals for the fur trade is grueling work that whites would not do. The U.S. Government ran the system for private fur companies until 1966 – after Alaska was a state – when the Unangan finally won the rights of citizenship, including the right to vote. Ilarion was born on St. Paul Island in the Bering Sea, to parents enslaved in the fur seal system. The U.S. Government minimized costs by being lax about the quality of children’s education, health care, or anything else.

So Ilarion grew up in the Unangan tradition, learning to sense all nature around him: where animals were, on land or under water, how to navigate in the sea without GPS or compass. He became fully enveloped in the nature surrounding him.

But little Ilarion was also a smart kid. He taught himself to read from comic books at age 5, and eventually graduated from the University of Washington. And he grew up subject to the abuses of agencies that did not regard the Unangan as fully human; therefore in need to their guidance. This bureaucracy has not worked well for anyone involved. The emotions of subjugation and separation left Ilarion with scars that took decades to pass. He had two failed marriages that he attributes to his inability to sense his mates needs.

Many of the Native American’s problems are legacies from families being separated, cultures and languages being suppressed, treaties being broken, and being confined to reservations that are not on highly productive land. For example, in Ilarion’s experience, many addictions are an attempt to escape present reality. Shaming or blaming the addict does not help. Ilarion learned a lot of lessons the hard way.

Along the way, he ran a trading store. He became mayor of a fishing village mired in many problems, alcoholism, drunken commercial fisherman coming ashore, and disposal of wrecked vessels. Official bureaucracy was no help, and often an obstacle. That is, in three or four decades he had “seen it all” while learning how tribal elders wisely resolved problems.

Several examples of this wisdom are cited, but one was an election in which opponents were smearing each other, which was opening a schism in the tribe. Some elders arranged a meeting in which the candidates would face off according the elders’ rules of debate: each candidate had to explain why his opponent was well qualified for the position. They did, and the schism disappeared.

The Unangan’s deepest problem is expanding human populations on islands beset by declining sea catch populations. In the Bering Sea you can see and feel climate change. There’s no doubt about it, science or no science. So after 40 years or so, Ilarion was “voted off the island” to become an elder of all the Alaskan tribes and a leader of indigenous people everywhere.

In November, Ilarion and other indigenous leaders are arranging a meeting of at least 500 indigenous elders from around the world in Hawaii. They do not know what will result, but they hope to stir global interest in voices and viewpoints seldom heard in any media, except that they are “protesting something.”

Last week, I had an hour’s conversation with Ilarion. I briefly explained the Compression Institute and Compression Thinking, and he could relate. Then I asked how he exercised the wisdom of an elder. “Never go into a meeting with prepared notes. No technique is effective unless you are genuinely concerned about each person as a fellow human being, flaws and all. If you feel this connection, a technique will occur to you when needed.” Ilarion has never had this approach fail.