Innovation is widely regarded as the key to the future. Almost everyone wants to promote innovation, but nearly all of us dislike change disrupting our life. So why must we innovate? Beyond the sheer joy of being cool, why innovate?

Promoters of innovation note that more of it occurs in urban areas where a greater population mixes more ideas, integrating bits of prior art into a refreshed mix. Denser idea mixing is more likely in New York City than in Shirkieville, Indiana, but population density alone does not do it. A crowd may consist of non-communicative strangers. The key is a higher density of idea mixes, and a greater diversity of ideas. For some purposes, mixing it up on-line may partly compensate for lack of physical proximity, as with open source idea systems.

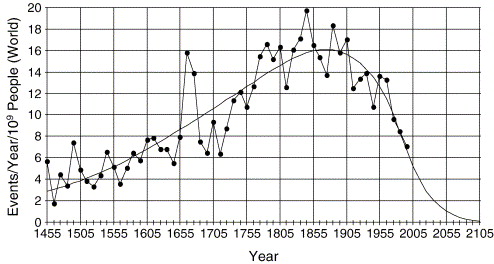

Some people look at innovation in new ways (that’s a novel thought). One is Jonathan Huebner, who proposed a theory contrary to idea density by identifying innovative events in world history and plotting them against global population. Heubner’s graph of significant innovations per person suggests a golden age of innovation peaking over a century ago – provided you agree that steam power and electricity were bigger disruptions than cool electronic communications. Critics panned Heubner’s subjectivity, but give him credit for daring to propose an alternate view.

If we are to be imaginative coping with a 21st century world beset by potential calamities, it is past time to ask basic questions: What must we do and why must we innovate?

What is innovation? How do we judge whether an innovation is “good or bad?” Can we anticipate an innovation’s long-term consequences, “good or bad?” Can we separate hype from “true innovation?” Issues sprawl in every direction, so defining innovation without using value judgments may be impossible even when we think are totally objective.

Most definitions of innovation, like that in Wikipedia, have a commercial and industrial bias. They presume that innovations spring from those institutions. Most definitions also note that discoveries or inventions do not become innovations until they change what people do. From a commercial viewpoint, we then assume that innovation is something that disrupts an old market or creates a new one. We may even presume that an indicator of a significant innovation is whether a company makes a pile of money off it.

However, if an isolated village in the Andes adopts a way to waste less water irrigating its own terraced fields, does that qualify as an innovation, or is an innovation significant only if billions of people buy cell phones? Suppose a wiring harness designer whacks ten pounds off automotive curb weight, but no driver notices the difference. Is this an innovation? If auto designers add back the ten pounds in new features that drivers notice, did the harness design enable innovation? Left hanging is whether the features changed behavior in a useful way, or were just come-ons appealing to a wider market segment.

Is there such a thing as purely social innovation, like a new dance? For instance, the Harlem Shake is a social innovation, but was it influenced by contemporary musical technology? Perhaps we can conclude that innovation is human change, with technology playing any role from main prop to an abetting influence.

“Adoption of a new technology” is an attempt to define innovation in a value free way. Then only technology users, not its inventors, need consider values when deciding on use and potential consequences. However, innovations are motivated by someone’s idea of people doing something differently. Motivations are not values free. In addition, many innovations are like gunpowder, which certainly had mixed “benefits:” those using it saved millions of “our side’s” lives; those blasted by it perished.

So what values today guide development of drone technology? Stem cells? Viagra? Computer games? Traded financial derivatives? And the myth of value free objectivity can be seen in the gun industry’s arguments with proponents of stiffer firearms control.

Innovations occur for a reason – somebody is motivated to do something differently. Values motivate diligence not only foreseeing benefits, but foreseeing downsides. Values motivate taking responsibility for downsides not foreseen. Taking such responsibility is becoming more complex.

Environmental and safety factors that we should consider are growing rapidly. Many of them must be considered in a total system context, much like taking prescription drugs. Single drugs may have side effects, and multiple drugs have interactive effects, and each body they go into is a unique complex system. Finance, law, and taxation are also complex systems. Nature certainly is, and with all complex systems, correcting one problem may jolt the system into another state with more problems to fix.

Despite these caveats, we must innovate – do a lot of changing – to cope with 21st century issues. Contending with constant change is the price we must pay, but most of us prefer to defer payment. We have to exchange the comfort of the status quo for the constant work of creating constant change. This work is partly mental; partly emotional. Mental work is constant learning of the new – and unlearning of the old. Emotional work is harder: it is to constantly value the future more passionately than the present.

Jeff DeGraff, a professor at the University of Michigan known for promoting innovation, recently reinforced this point in a wordy mea culpa on his own hypocrisy, a hypocrisy that nearly all of us innovation lovers share. Jeff’s wake up call struck many personal nerves: “You will never make way for the new, the deviant, the subversive until you are willing to destroy the very things you have spent your career creating.”

To meet the 21st century challenges of Compression, innovation is desperately needed. Whether with novel technology or not, we must fundamentally change what we do. But do that, we must deeply question the values motivating innovation. For example, even when we think that we are going to prolong excess consumption on an energy base of alternate fuels, low returns on energy invested make that dubious. And time is short. If we were all passionately aligned, change would take years.

We dally because all of us cling to the past to some degree or another. Clarity, alignment, and commitment are tough issues coming out of the box. Many organizations are working to make pieces and parts of our necessary conversion happen, but nearly all of us are also clinging to mindsets that are rapidly becoming obsolete.

Unfortunately, our old comfort zones are leaving us. Clashes in values are the new normal. There are risks. Stick your neck out; expect your head to be a target. Few revolutions occur without of some of the revolutionaries being casualties.