Or What’s Objectivity in Journalism, Science, and Life?

The ending of Propaganda Blitz, reviewed previously, digs deep into objectivity in journalism. What is it? To answer this question, the authors, David Edwards and David Cromwell, cite ancient philosophers, mainly Oriental ones. They conclude that commercially funded journalism is trapped in the box of business rationality. Their final musings apply to more fields than journalism. Their philosophy of operating Media Lens to critique media veracity is a “no-business business model.” They refuse corporate money and corporate philanthropy, and thereby try to see the world outside the box of business thinking, however indirect that influence may be.

What this means dear reader is that if you want the news as straight up as you can get it, prepare to pay for it. I personally pay for news from a few sites that do not have a “mainstream perspective.” Edwards and Cromwell aver that that perspective sells “corporate-owned politics, perpetual war, unsustainable materialism, and climate disaster.”

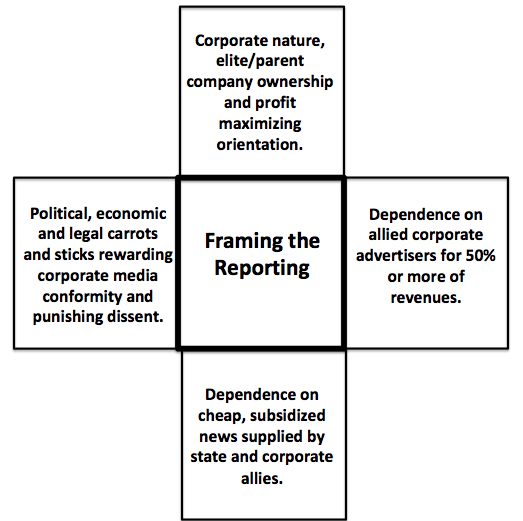

And why do corporate-supported media do this? Edwards and Cromwell posit a four-sided wooden framework, a box that frames what media do and don’t report, and the perspective from which they report it:

To cut to the chase, a corporate media reporter cannot imply that the incentives of either the system or its supporting governments are flawed. She can only state that a company or a person has violated its laws or conventions. She can be objective if doing so does not offend the powerful or their system. For instance, reporting that any service of the Cuban government works well has to be countered with a “however.” Impartiality has to be carefully bounded.

If a “journalist” merely craves more eyeballs, she can cherry pick half-baked scientific studies and generalize startling conclusions. If you have 19 minutes to spare, John Oliver has a hilarious send up of this phenomenon on YouTube.

However, seemingly serious journalism does more damage. Impartial coverage is not sterile detachment, merely transcribing what was said or done. Fact checking is mandatory in egregious cases (of which there are many these days), but the validity of fundamental premises is not questioned. That means giving voice, for example, to climate change deniers even when their evidence has been discredited.

So what is objective reporting? For that, Edwards and Cromwell turn to Buddhist philosophy, and come out positing that objective reporting is rooted in two ideas:

- That human beings are able to view the happiness and suffering of others as being of equal importance to their own.

- That, perhaps counter-intuitively for a society like ours, individuals and societies dramatically enhance their well-being when they “equalize self and other” by caring for others in this way.

A reporter grounded in these ideas does not refuse to stand in judgment of our leaders while condemning their leaders, holding “them” to a higher moral standard than “us.” It’s a beginning toward a code for a tribe of the whole, or perhaps a tribe forthe whole, since few of us can fully shed our tribal culture. However, we might be able to interact through an ethical overlay across the tribes.

Now refer back to the box figure for a thought exercise. That figure was designed and labeled for corporate influenced journalists. What field of endeavor are you in? If you are in a box hemmed in by corporate think, can you label the boundaries? What box are educators in? Physicians? Border patrol officers? Trial judges? Environmentalists? And what box are you in. (Personally, I’ve reasoned from a business framework perspective most of my life; can’t function in this society without doing so, and thus struggle to see from outside that box. I’m guessing that most readers are in the same boat.)

We are not going to make significant progress on environmental challenges without escaping such a box if we are in one. How would you frame a box in which nature’s needs bound its walls?