A New Myth (Video 5 minutes)

A New Mythology for the 21st Century

Say “mythology” and we think of Greek mythology or indigenous tribal stories, but we think we follow facts and logic. Actually the 21st century is soaked in myths that we follow more than we think. When facts confuse and emotions tug, we go with the gut, as when agonizing whether to pull the plug on a loved one’s life.

Serious myths frame serious decisions. Some myths seem so self-evident that we rarely question them. One is endless economic growth. Another is that no system can beat free market economies. A third is that technology can solve any problem. From these, a fourth follows: “”Human nature is what it is, improvable only through transhumanism or our“tribe’s” existing religionmythology. Hokum. We can fix ourselves for the better, partly by adopting a new mythology from a new perspective. For that let’s turn to space.

Spaceship Economics

Imagine a spaceship deep in space, too far out for resupply from Mother Earth. It must capture energy from local stars and convert it to a form that preserves human lives on the ship indefinitely. What culture could real humans invent to do that? And how?

Nature long ago invented how. We call it life, all life, not just human life. Totally understanding all life is beyond real humans, even if we are in space. Myths to guide spacemen through fogs of limited understanding would be unlike trite sci-fi plots: conflicts with alien forces much like human tribal warfare. Instead, spacemen would more likely concentrate on maintaining alllife aboard the ship because they utterly depended on it. They would need myths from that perspective.

We live on a spaceship now, but unlike Buckminster Fuller, few of us recognize it. Historically, earthly tribes utterly depended on nature, so they had to respect it, all the while also competing with other tribes. Now our technical ability to disrupt nature is far beyond that of indigenous tribes, but our myths still deceive us that all the rest of life on an infinite earth exists for us to exploit. Surely we can abide by our old myths and “save nature” too. Not really. We need a new guiding mythology, one that shifts our perspective of what we are and what we must do to survive. But first what are myths?

What Do Myths Do for Us?

Some myths inspire; others warn. All have a moral, like fairy tales. Well known myths include: Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, the Loch Ness monster, Big Foot, and UFOs. Storytellers “juice” actual events, sometimes fuzzed by grainy photos, into myths. Retelling pumps more juice and spawns offshoot tales.

Fear myths often juice safety warnings; two girls last seen hitchhiking were found months later, beheaded (don’t hitchhike); a plating factory worker went missing until a lab test of acid revealed that contaminants in one of the tanks had to be his remains (don’t clamber around over open tanks).

Until evidence conclusively supports them, scientific theories are little more than knowledgeable myths. We cannot personally verify all scientific findings. Whether we act on them depends on whether we trust the sources – and whether they accord with other myths that we live by. But is data cherry picked to confirm a bias? Do study designs elicit conclusive evidence? No individual can check all studies; we have to trust the integrity of those who do, and they need to feel an obligation to do it.

Political movements are largely myth breaking and mythmaking. So is commercial marketing. Building a brand is a form of mythmaking. Twenty-first century populaces swim in an ocean of myths, many of them concocted for fun and profit.

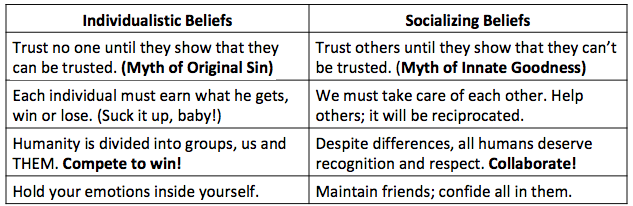

And way down deep, so deep that we may be unconscious of them, fundamental myths and beliefs shape our souls. Personal myths influence how we regard others, whether we are a fighter or a milquetoast, etc. Any list of personal myths is necessarily incomplete, so Figure 1 only illustrates a few, organized to contradict each other.

Figure 1. A Few Deep, Personal Myths

Few people consistently exhibit one of these contradictory myths. We deceptively pose as social while trusting only ourselves. For example, a boss may repeatedly tell employees that she trusts them completely, all the while monitoring software that captures every keystroke. Human behavior being duplicitous, we constantly “sniff each other out.” Human trust Is hard to build and easy to destroy.

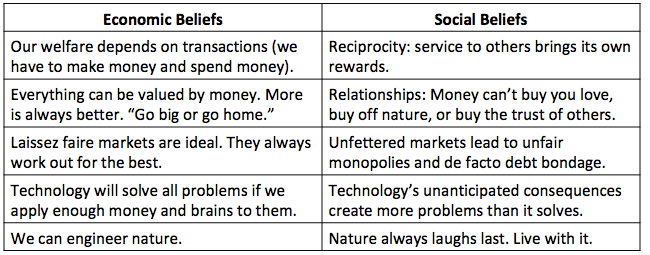

Besides personal myths, there are social myths, mostly learned from others. Figure 2 contrasts a few contradictory ones. Few people exclusively believe any of these either. Most of us navigate life drawing on those that seem to fit the situation.

Figure 2. Some Contrasting Social Myths

What Makes a Myth Useful?

Paradoxically, myths buttress a stable society. That society may be terribly inequitable by our beliefs, like medieval feudalism, but it is stable in form. A society’s myths sustain trust that others will perform the functions needed for all to survive, if not thrive. In modern nation states, myths stabilize three critical functions: security in distress (wars and disasters), legitimacy of governance, and confidence using money for trading.

When they cease to offer good guidance, social myths fade away, but don’t die. People in cultural turmoil revive them when rummaging for alternative explanations. Perhaps we are in cultural turmoil now; even the Flat Earth Society is making a comeback.

Besides income inequality, a big reason for cultural turmoil is deteriorating global ecology. It affects some at a crisis level while others barely notice it. This presents a global quandary for all mankind. We struggle to even recognize it because we have long resolved problems piecemeal, as tribes, companies, localities, or nations. Our economies promote growth in physical consumption of energy, materials, and toxins. Our myths support these systems by touting a better life for all by growing the economies of tribes, companies, localities, and nations. Global ecology is a much longer-term mutual human responsibility, but economic myths don’t motivate us to safeguard nature as well as ourselves.

Myths to Support Compression Thinking

Success stories persuade people to try new ideas. They describe how new ideas work and how they affect people. If juiced, success stories morph into motivational myths. Right now, environmental success stories are embryonic, like that of the Isle of Eigg, nearly self sufficient, but Eigg is too different from most of earth to motivate action worldwide. However, its story does illustrate that ecological regeneration depends on more than techniques. New human concepts of success and quality of life must wean us off monetization and consumerism. Myths to promote Compression Thinking need to address a few key themes:

- 1. Earth is finite. We must cut consumption, and in advanced economies, dramatically. Despite overwhelming evidence, this necessity has not generated convincing myths.

- We are part of nature and it is our teacher, so pay attention.

- All humanity is in this together; stop abusing nature with human win/lose games.

- Safeguard all life: preserve the health of nature, so it preserves us.

- Life satisfaction is from serving social and ecological good, not from acquiring “stuff.”

- Learn to reason by evidence using scientific methodology and systemic thinking, with nature as a reference. (Science suffers from fragmented studies and monetary biases.)

- Create human trust to collectively learn what we cannot master independently.

Paradoxically, myths with these themes would emotionally stir us to learn based on evidence – allavailable evidence. Vigorous Learningsorts out, not just evidence, but conflicting beliefs or myths for interpreting it. Myths to support Vigorous Learning would herald a profound change in the capability of the human race, a maturing beyond myths that promote conflict. Can we re-conceptualize what it means to be human? Can we transform ourselves to live with nature? The prognosis is not rosy, but all alternatives seem destined to leave humanity deep in space futilely wrestling our emerging perils.