The world is full of environmental movements. Some like the World Wildlife Federation, Worldwatch Institute, and The Rocky Mountain Institute are well established, each in its way undertaking “doable” projects to better the environment. Activist movements like State of the World Forum and 350.org keep political pots stirred. More such organizations than anyone can track are all oozing toward similar goals, but they are small compared with companies and governments whose value systems are based on continued economic expansion and consumption of resources.

Given all this activity, why mull over Compression Thinking? First, the need to cope with resource depletion rests on too many indicators of trouble to stay in denial of them all. Second, organizations gobbling resources must volitionally apply imagination to this situation, not wait to be regulated; then foot drag. Third, many leaders think that action is complicated and adds cost to consumption processes as they are today, so they seek magic technology or pretend that nothing needs to change. Fourth, without a relatively simple goal that everyone can grasp, concerted action is difficult within small organizations, and impossible for global industries. Such considerations led to the “operational goal” of Compression. A version updated from the book as follows:

“By 2040 globally improve the quality of life to an industrial society equivalent using no more than half the virgin raw materials and half the energy as in the year 2000, and with no known toxic releases.”

OK, this is arbitrary. Most scientific observations and projections that support it are approximations, not pinpoint numbers, but too many line up in an unfavorable direction. Simply cutting resource use diminishes every other problem. If there were there no consequences, unnecessary consumption of resources makes no sense anyway. The above statement meets is operative in the sense of defining something to do by when, with progress being measureable in milestones.

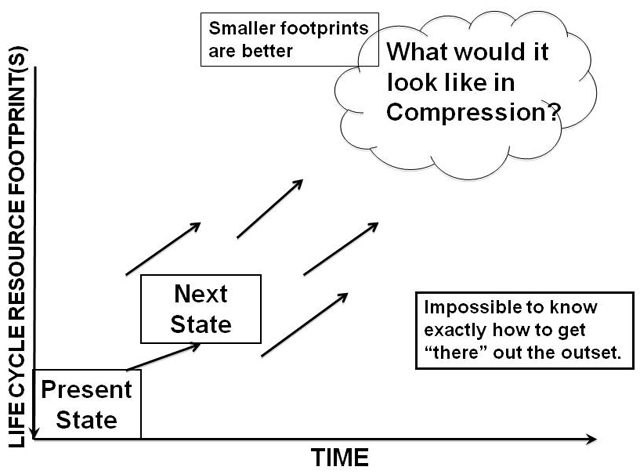

However, by being operational, this objective is too abstract and complex to be a theme for a pep rally. Its implications take thought. Those who do may be able to construct missions, goals, and operational programs for work organizations based on it, somewhat as shown in the figure. Those will vary. For example the overall goal is global, so in high consumption regions, resource reduction has to exceed 50 percent. But low consumption regions barely skimp by now. They can’t cut much, but may be able to more effectively use resources at hand – stop waste that makes the situation worse.

But the deepest implications transform cultures where using more is a mark of distinction into ones where wisdom doing more while using less is highly prized – a values shift. Inner change is difficult, learned by adopting new habits and skills that displace old.

We have tools and means, and we can invent more, but our old expansionary thinking inhibits us from using them. And to engage in rapid learning, we must learn to work around human flaws and limitations, both as individuals and as organizations. In this arena, conditions change, countermeasures may not work out as planned, or just give rise to a new set of problems. We really do have to constantly compare actions with consequences, never assuming that “we have it made.” If we can learn to do that, we can get on with it.