Predicament of Mankind (Video 7 minutes)

The Predicament of Mankind: Searching for Causality

by Doc Hall

Many more issues threaten the environment than climate change, although that one exacerbates all others, and it dominates environmental reporting. The enormity of the social upheaval to mitigate these threats boggles the mind, and imagining Armageddon is depressing. Most of us put this “unspeakable dread” out of mind by denying it or by giving it such low priority that it can be infinitely postponed. Surely, anything disrupting my company or our wonderful economy is an attack on our way of life that we must resist.

This dread has festered at least since The Limits to Growth (1972), which came out of the Club of Rome’s “Predicament of Mankind” project. That project’s proposal paper in 1970 recognized that the roots of our predicament extend beyond climate change to mankind’s social and political ills, exemplified by a list of 49 human problems. None of them have been resolved, and we don’t have 48 more years to debate issues.

Today, in our social confusion, many people believe that old economic nostrums, only better, will restore good times as they remember them. Others are confident that technical genius will resolve any problem, big or small. Even the most dedicated environmentalists can’t imagine an upside-down world where today’s concepts of success lead to disaster. That is, our biggest environmental problem really is us. If we can accept that we made our mess, it follows that we have to fix the mess.

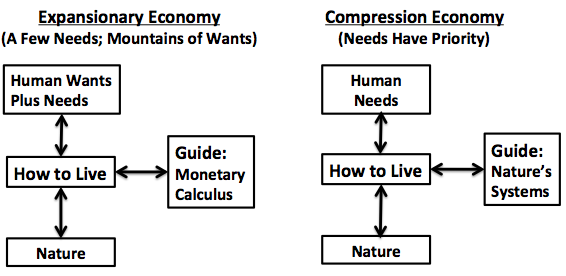

Others are starting to think this way. “Radical adaptation” is one of many terms to describe a bigger and faster shift in how we think about challenges than has ever occurred before. What must we do? First, distinguish what’s vital to our wellbeing from everything not essential to it. Eliminating our non-essential consumption is implied in Compression Thinkingand by Figure 1 below. However, we resist being deprived of any consumption we now enjoy. That’s the heart of The Predicament of Mankind.

Figure 1.Whether analysis is guided by money or nature makes a big difference.

What’s essential to our existence is preserving all life because human life relies on all other life. Preserving human life is instinctive to most of us; preserving all life is not. To survive, our essentials are: Food, clothing, shelter, health, reproduction, developing the young, and entertainment that does not squander resources. However, few of us are content to live in survival mode. Distinguishing frills from essentials is no small matter.

In plain talk, first we need a purpose in life beyond the bottom line and grubbing for money. Eliminate “bullshit” that consumes resources, but doesn’t preserve the wellbeing of either humans or the environment.

Second, we must do much better determining cause and effect, which is the primary objective of learning by experience. From PDCA logic loops to multivariate statistics to structured dialogic design, techniques abound, but we’re still lousy at it. Emotions and illusions distract us. One more time, a way to describe a learning process is:

- In detail, how do processes work? (When you know more, you can draw on more.)

- What causes what? (Chains and loops of antecedents and consequences.)

- How will an intervention change the system?” (Predict consequences.)

Causal Connections

Sometimes humans instinctively solve problems, but much of the time we have to battle our instincts to concentrate on causes and effects. An egregious example of failing to do so is someone reporting a crime, real or imagined. Fingers point to a suspect considered low-life because of race, religion, or reputation. Accusers need meager evidence – or none – to convict them. Without digging deeply into factual evidence, they eagerly embrace emotional closure by “doing something about it”.

Most of us would not railroad a suspect, but all of us are biased, including professionals. We all have confirmation bias. We see what we hope to see. We are myopic seeing evidence we do not wish to see, or do not expect to see.

And all of us battle mental laziness, short circuiting logic to avoid spending the time and energy to understand a matter. Time frequently presses us for a decision in the absence of facts. Much of this pressure we artificially bring on ourselves, as with construction projects having time and cost budgets (in business, “time is money”).

Burden of proof is another battle. In court, the burden of proof is presumably on the prosecution or the plaintiff. The Precautionary Principleflips this burden to the takers of action – or the defendants – to show that to the best of their ability their action will not harm other humans or the environment. By legal logic, that’s like being guilty unless you prove yourself innocent. But when consequences are dire, the precautionary burden should weigh on decision logic all the way through projects of consequence.

Will this slow a great deal of “economic development?” Absolutely. Given the state of the environment, projects should go for quality over quantity, always, one of the principles of Compression Thinking.

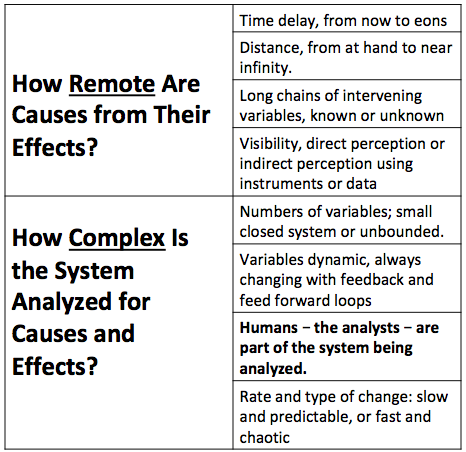

Figure 2. Huge differences in situations when analyzing cause and effect.

Figure 2 is abstract, general, and dull until you are personally involved seeking causality. Then it becomes intense. It’s hard to control one’s self and exercise imagination by a logical framework as if you were dispassionately objective.

For example, a messy quest is why so many young adults who had been troubled youth and alumni of a troubled school, the Family Foundation School, are dying way before their time, often by suicide. Was it their precondition, the school, or factors from both?

Data are scanty. If the school was ever organized to learn what worked or didn’t work, little trace is left. (If you are confident you already know how to do something, why learn more?) In addition, the investigators are alumni of a school that is now closed, researching their own condition. Human interest makes this a good story, but how rigorously are the alumni researching this morass of possible causality?

We are seldom well organized or disciplined to learn – to sort out cause and effect – unless we structure work ahead of a crisis as a vigorous learning organization. At a minimum document what we did so we are not guessing later. And we would like to eliminate situations in which “defendants” of action obfuscate and delay, as in the long investigations linking lung cancer to smoking.

Few people will dispute evidence that anyone can see (the flood rose two feet in my house). Whether a future flood will reach a house never before flooded is more uncertain. What evidence from many sources points toward floods rising ever higher?

One example of phenomena we poorly understand is the effects of solar flares on earth’s weather, climate, and technology. Prying into this is the mission of NASA’s Parker Solar Probe. That’s true science, discovering and defining previously unknown phenomena; then analyzing for cause and effect.

We expect that of science. We should learn to expect everyone to become a scientist investigating causality within seemingly mundane matters on earth that are crucial to human and ecological wellbeing. Here’s a sample list of such matters:

- Indoor cleaning; effects on health; what does clean mean; can you be too clean?

- Growing more nutritious food crops using less energy and fewer toxins.

- Using much less energy to warm or cool a living area.

- Reducing household water use.

- Determining a nutritious diet unique to one person – you.

The number of reminders about rigorously investigating cause and effect seem endless. Don’t jump to conclusions. Don’t generalize from specifics. Beware of unknown intermediate causes. Clarify a suspected causal linkage with a simple diagram. Probe your own assumptions as well as those of others. Pin down what evidence is needed or necessary to “prove” a causal linkage. There are a welter of such reminders.

What’s Our Predicament?

Although foggy on the causal connecting links, many Club of Rome investigators sensed decades ago that our environmental problems stem from the emotions, illusions, and economic mythologies that guide us. Others have come to that conclusion since, but we’re no closer than in 1970 to resolving how to upgrade to Humanity 4.0.

Discipline to deeply understand causality would be a major step in that upgrade. Can we do this? If so, how, because our humanity works against us? We have techniques. We have experts. What we lack is a movement to draw citizens of the world away from emotional distractions, toward becoming experts themselves. We lack a pathway to accomplish that. The future of mankind depends on us finding one.

Will you start with us finding that pathway? Or, as environmental and behavioral pessimists predict, will only a savage remnant of humanity survive the 21stcentury?