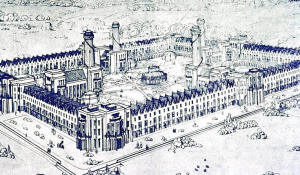

Robert Owens’ Vision of Utopia — New Harmony How it Actually Turned Out

Robert Owens’ New Harmony in Indiana is a 19th century cautionary tale about visions and utopias. A sect of Harmonists before Owens consisted of farmers and craftsmen — doers. Owens brought in a cadre of intellectuals and dreamers. The Harmonists succeeded. Owens failed. Nonetheless we need a “vision” in order to succeed at anything difficult to do because it is different.

Suppose that it is 2050 and we have successfully met the challenge of living better while using perhaps a fourth of the raw energy and material resources of today. What would the world look like?

While a precise picture cannot be drawn, a few starting points are obvious. Re-use and recycling would primarily provide the things we use. We would concentrate more on maintaining everything from roadways to kitchen faucets. We would work and play closer to home. Energy sipping vehicles would not be driven as far. Consequently, much innovation would be do-it-yourself retrofitted, adapting our gadgets to different uses, perhaps with downloaded software and 3D manufacturing. Much less food would ship long distances. And we would heat and cool less space much more efficiently.

Social changes might seem dicey, but a few would have to come to pass. For example, if most of us lived in good health until about age 90, our age demographic would be nearly flat – more “retirees” than school kids. However, retired might not mean exiting a day job, like today, but a gradual change toward less physically stressful responsibilities. This in turn presumes a true shift toward preventive health care throughout life, and less time in aged debilitation. This would transform the assumptions of both retirement plans and health insurance.

At the other end of the age scale, what would prepare children for life? Possibly more engagement with the adult world, with formal schooling more integrated with activities learning how to care for the world they are inheriting – extended internships.

And if we improve quality of life, what does that mean? There are common indicators like infant mortality, days spent sick, adequate nutrition, access to clean water, and the like. Beyond that, some of us like extreme sports, some entertainment, and others have hobbies. Doubtless, some will also be troubled with substance abuse, marital problems, and personal issues, just as today – or 100 years ago. And the world will still have some form of wars and disputes. Utopias are mirages, but maybe we can figure out how to restrain our strife so that we don’t destroy the planet with it.

But a very significant social shift is apt to be toward more community-centered social units and toward more personal responsibility for those around us and for the planet. That is a prescription for building a new “middle class” on a different basis, beginning where we are with what we have.

To do this we need a major movement in communities to develop clarity of thinking about where we are going and how to resolve our problems getting there. This new world promises to be one in which life is often disrupted by storms, flooding, draught, fire, etc. Creating communities that are both physically and socially robust in recurring disasters is also going to shape how we socially evolve.

To make this transformation, we need to use our “optimism biases” wisely. Optimism bias is underestimating risks of negative events – thinking that “it” can’t happen to me. Tali Sharot and other researchers on optimism bias consider it to be psychologically necessary for our survival. In bad circumstances it motivate us to persist with difficult challenges.

However, optimism bias also creates euphoric bubbles, and an inclination to ignore facts that pop them. Consequently, we ignore evidence until crisis envelops us. Tali Sharot notes how a double case of this led to the misery of WWII. Stalin, trusting that Hitler would not invade the Soviet Union, ignored intelligence that nailed the exact date. In turn, Hitler in his exuberance blew off warnings that the invasion would be, not easy, but a slog in a bitter cold winter.

In retrospect, maybe Hitler and Stalin deserved each other, but the rest of us deserved better than to be dragged into the consequences of their psychoses. With pragmatic effort, we can make a positive vision triumph over misplaced nostalgia for a world that is going away. And that is why we propose a vision of better living, using less through “vigorous learning organizations” that employ Compression Thinking.