Are We All Avatars in a Big Simulation?

Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard, translated by Jean Glaser and Sheila Faria Baudrillard

Jean Baudrillard was a French philosopher, a contributor to post-structuralism, along with the better-known Jacques Derrida. This bores anyone not deep into philosophy, so why dig into it? Because Simulacra and Simulation is mentioned in the movie, The Matrix, which is becoming a classic among people questioning all authenticity in an on-line world, and this book partly inspired it. The plot of The Matrix hinges on people being unaware that they are interacting with an alien, faux world, not reality, somewhat like Orwell’s 1984 earlier.

So if Simulacra and Simulation inspired The Matrix, what did the horse’s mouth say? Practically nothing; that’s the point. Baudrillard posited that we create meaning only by symbols referencing other symbols in a pattern that makes sense to us. None of it may represent reality, if there is such a thing. Consequently he is an expert turning logic in loops, citing referential contradictions, and doubling logic back on itself.

Simulacra and Simulation is an eye glazer. Its opening attributes to Ecclesiastes the observation that, “the simulacrum (a representation) never hides the truth – it is truth that hides the fact that there is none.” (I could not find this in Ecclesiastes, but suspect that Baudrillard refers to its refrain that of much study there is no end; all is vanity.)

Baudrillard harps on “hyperreality,” symbolism as in videos, whereby images seem more real than whatever they represent. It’s like seeing a video of a resort only to find that the real resort, if such really exists, is much less elegant than the video. He claims that hyperreality is the medium by which humans communicate, so it’s not new, but with modern media, we swim in an ocean of hyperreal nothingness.

Incidentally, Baudrillard did not mention The Matrix, but cited the 1996 British-Canadian movie, Crash, as one that approached seeing reality through the superficiality. The plot hinges on people being sexually aroused by fatal car crashes, either as victims or as witnesses. For Baudrillard, coupling sex and death in one emotional smash up invokes the full circle of life – but this combination didn’t particularly grip me.

I could not follow many of Baudrillard reversals of logic. The impression left, and perhaps the one he intended, is that post-modern, post-structuralism humans live mostly in our own simulations, subject to chaotic flips in meaning as discordant images flash by. You can see this in pop up ads and promos, all trying to out-gimmick the others. Is this a race to symbolic nowhere, an inane mashup of personal and corporate brands, never escaping Solomon’s conclusion in Ecclesiastes, that all is vanity?

Anticipating relief from this depressing thought, I started Baudrillard’s chapter on animals – nature – something other than Mobius strip loops of symbolic logic in media. Immediately, he dived into the mental health of animals in industrial feeding enclosures. “Democratic” access to food, so all animals will grow, screws up animal instinct for a pecking order. Confinement to tight spaces raises anxiety. Birds go nuts. So do other confined animals, whether farmed or merely observed, as in a zoo. Veterinarians have come to realize that animals in a non-natural environment are mentally distressed. They also get cancer, ulcers, and myocardial infarctions. Research vets think that turning them back into the wild once in a while might preserve their mental and physical health.

Baudrillard opines that everything that has happened to us is now replicated in confined animals. Ne notes that the ancients who sacrificed animals to gods must have valued them more than moderns. Sacrificing an objectified critter does not seem emotional enough to appease a god. Baudrillard suggests that sacrifice is at least a meaningful loss. Now we have relegated animals to detached roles of being food or pets or objects of experimentation and casual curiosity. How would humans in such roles react?

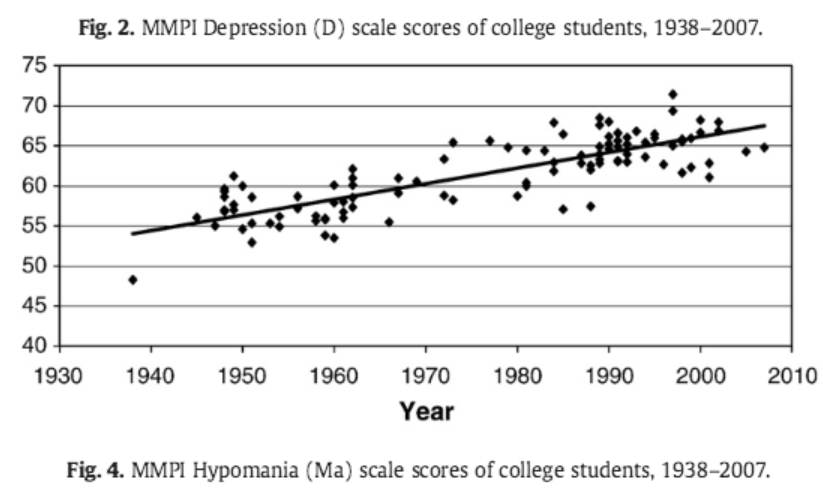

This suggests a line of study that has been emerging since Baudrillard’s death in 2007, increased depression in American youth. Some blame addiction to cell phones, social media and computer games, but the trend began long before those arrived according to an old study led by Jean Twenge. The figure from it below plots data over a 70-year span.

Speculation about this phenomenon keeps increasing. Youth are more self-centered, anti-social, anxious, and sad. And the phenomenon may not be confined to youth. So what is happening to us? What about the march toward a mobile, connected, and for some, affluent society might be a cause.

Maybe in all Baudrillard’s logical looping, he had a point. If we’re not living close to how nature designed us, we can become distressed. Many urban planners have sensed this ever since the 19th century, insisting that in their rush to riches, cities leave plenty of space for nature. These might do nature a little good, and us a great deal of good.