The Compression Institute is embarking on a series of dialogs seeking how to break through the lethargy that prevents us from taking action on “Compression.”

We have made many wonderful advances, but they do not begin to address Compression, which refers to human consumption depleting many resources on which we now depend and using them to foul the environment on a big scale. But our inability to comprehend the scope of the mess we are in and take action is as big a problem as the mess itself.

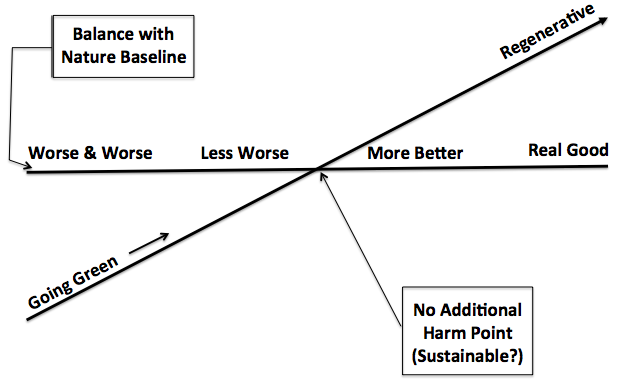

The figure below is a Yogi Berra interpretation of what is and isn’t happening:

The figure spoofs a diagram by Bill Reed, Trajectory of Environmentally Responsible Design. Ponder, and you may recognize some implications of this diagram. For example, one is that moving left in the diagram takes more and more energy; moving right takes less energy consumption. (Yogi’s double-take insights are what make him charming.)

That is, the heart of human issues with the environment is motivating urgency to reform processes that seem abstract, arcane, and distant. Once aware of this conundrum, you can regularly spot news squibs relating to Compression. However, most of them quickly sink to the bottom of the clutter in mainline news, which emphasizes issues to which people can more easily relate. One of those is daily reporting on growth of the economy. The economy is also a murky abstraction, but people cocooned in the institutions of a commercial economy can more easily identify with it.

There are many reasons why the public, decision makers, and even environmentalists underestimate the depth of our mess. Environmental news squibs are often depressing, while psychologically we must maintain optimism. (About 900 people will die in traffic today. So what? Not me. Without that confidence, I might not get out of bed.)

Just to deepen depression, here are a couple more factoids:

Five years ago a science reporter estimated that only 16 big ships annually release as much sulfurous oxide as all the world’s vehicles, and thousands of these ships are in the global fleet. This estimate drew a drib of attention to the seriousness of maritime pollution. Formal studies didn’t. But have you ever seen the estimate – or any studies?

Five years ago, a report in Nature concluded that the plankton population in the ocean is dropping about 1% a year, conjecturing that in 40-50 years, plankton may have already decreased by 40%, but no proof. Plankton being the base of the food chain, this is dead serious. A brief flurry of news items appeared. Remember any? A new report in Science now suggests that we still know too little about how the diversity and complexity of micro life in the oceans support us, and how we are affecting it. That is, ocean scientists know that we are screwing up, but not how badly, or how fast.

Making sense of science today depends on interpreting findings from many fragmented sources, and they take time to fall into a pattern – if they do. The public can grasp a 40% speculation – briefly – if they can imagine potential consequences. But explaining our utter dependence on complex biodiversity is not a conversation starter.

Fragmented scientific findings are often inconsistent. Reefs are dying. Wait a minute; in the right conditions they rebuild. Isolated findings are incomplete, but to the public, faux confidence based on ignorant assumptions is more convincing than the uncertainty of fragmented investigations to determine factual reality. Putting a picture together is slow.

A good example of this is whether frozen methane in the melting arctic is a runaway adding greenhouse gas to the atmosphere, certainly a question is of great consequence. How drastic are the climate changes that we should prepare for?

The arctic stores over twice as much methane as is now in the atmosphere. Methane is a much more potent climate changer than CO2, but by how much is not agreed upon. If the arctic keeps warming rapidly, methane releases will increase, but how fast? A Washington Post article summarizes this situation.

This phenomenon is assuming urgency beyond academic curiosity, which normally drives the speed and funding of scientific inquiry. You can start tracking this in the Arctic News blog. May 2015 temperatures in Southern Alaska matched those in Texas. And among other tidbits just in, a study in Siberia found that bacteria decompose frozen carbon in exposed permafrost into CO2 (not methane) in just two weeks.

Scary stuff, but how do these findings fit with other observations, and are we observing enough? The effects of arctic melting being uncertain – still up in the air – they are not yet incorporated into those big models that project climate change. Our technology is more impressive than our ability to put a picture together.

But we should be more fearful of our own incapacity to deal with uncertain phenomena. That is the Compression Thinking Challenge. At its base is development of fundamentally better collective learning processes.