Finding Our Real Reserves

April 7, 2020

Covid-19 and its economic tailspin presage many more crises to come. We must change how we live and how we think. Our economic objectives have set us up for Covid-19, with more debacles on the way. What we have assumed to be success, isn’t.

We yearn to return to “normal,” but the system relies on constant cash flows. A pandemic shut down chokes cash flows. The system has too few reserves to cope with recurring crises. It can’t even foresee them. The system is also fragile. If throttled back for months, it would have to morph into something else. The system’s fatal assumption is that it can somehow float in its own artificial reality, taking from nature while giving little back. Covid-19 exposes the system’s weaknesses, and pandemics are only one item in a long list of environmental threats.

Congress’ $2.2 trillion aid package won’t prop up this system very long. Cash reserves and emergency loans are useful only if they can buy what is needed, when needed. Our real reserves are human skills, resourcefulness, adaptability, and teamwork. Economists call this social capital. It’s the opposite of insisting on individual rights, on “freedom” from anything we don’t like. For example, the NRA and gun groups are suing states for closing gun shops. Plastic bag companies lobby to stop banning single use plastic, alleging that reusable bags harbor more pathogens (little evidence). Stopping money flows, like regular bill payments, throws the system into turmoil. In an emergency, bidding, billing – the transactional system – slows action. Overcharging, “because of market demand” becomes a quasi-criminal act.

What would a new system look like? That’s for a future column. This is a backgrounder on virology and pandemics offering a glimpse of that future. It starts slow and builds up.

Coping with Pandemics

We’ve always had epidemics; they are part of nature. Worst were smallpox epidemics, all from very similar Variola viruses. Foggy data suggest high smallpox death rates — from 20% to 90% of infections. Because practices like hand washing were unknown until the mid-19thcentury, sporadic epidemics were lethal and regionally confined. They receded as survivors developed immunity. The European Black Plague in the 1300s was an epidemic because it could not jump to the Americas. Masses of people travelling all over earth turn an epidemic into a pandemic.

Europeans coming to the New World brought with them their diseases, notably smallpox, long a recurring scourge over Asia, Europe, and Africa. These were unknown to Native Americans, so they had zero immunity. Native Americans did not rove coast to coast, so 90% of them died in waves of regional epidemics over a course of 250 years or so, not in one big continental die-off. Globally, smallpox was such a killer that a campaign to eradicate it persisted throughout much of the 20thcentury. It succeeded, and now it’s a fading memory. So soon we forget.

Better sanitation, plus disease control, as with antibiotics, lulled us into thinking that science can instantly concoct miracles on demand. Between 1900 and 2020, these “miracles” doubled life expectancy for the entire world, one reason for global population growing about 5-fold during the same time. However, birth rates can’t exceed death rates indefinitely, so something must change – by intent or otherwise. Not only did we occupy more land for basic living space, we gobbled up land and resources to increase per capita consumption.

This overreach squeezed out a lot of other life, and it set the stage for pandemics. Animals crammed together create conditions to spark pandemics, and dense populations of mobile humans spread them further, faster. Similarly, in large scale monocrop agriculture newly evolved plant pests can destroy huge volumes of crops before a countermeasure can be fielded. Pandemics presage many other potential environmental calamities, so we should get ready.

The first big pandemic was the 1918 Spanish flu from the H1N1 virus, probably from a bird. (Virologists fear the H5N1 avian flu virus mutating and jumping to humans; very high fatality rates.) Pandemics are caused by a recently mutated virus that may further mutate as it spreads. Health authorities coping with an outbreak of a new virus must manage a learning experience, plus public misunderstanding of it. Autopsy evidence suggests that the H1N1 Spanish flu virus mutated as the flu spread. Early cases were mild, fall 1918 cases more lethal, and 1919 cases much milder, but immunity build-up and victim pre-conditions are also factors.

Data from the Spanish flu show conclusively that American cities that imposed separation rules early, and kept them longer, had fewer deaths per 100,000 population, a lesson long lost to all but epidemiologists. In any case, by 1920 Spanish flu was gone and soon forgotten. Also, epidemics of other diseases were a living memory, so Spanish flu seemed “normal; just bigger.”

Virology, Epidemics, and Pandemics

This is an amateur review, not by a professional virologist, but a few basics help us understand pandemics. Please do your own Googling of reliable sources.

A pandemic is the spread of a pathogen – an invasive species – to which a population has little or no prior immunity. By contrast, an endemic is recurring illness from a pathogen to which a population has resistance, by vaccination or by survivors’ immunity. Vaccination does not always confer immunity on every individual vaccinated. It makes a critical mass of people immune (herd immunity) so that contagion does not go wild (or “go viral”).

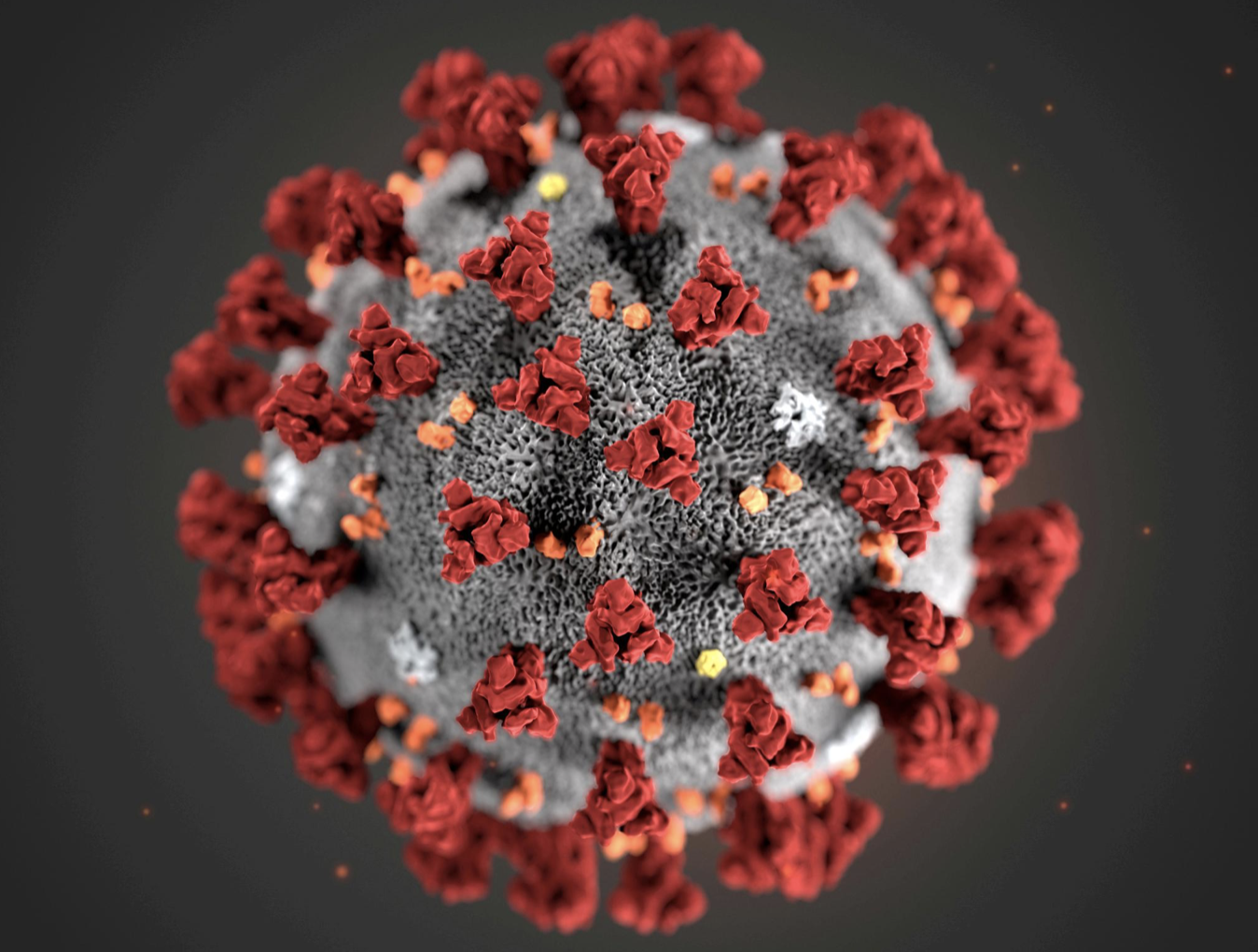

Pandemics start with a spark; then spread. A spark is a mutated virus infecting patient zero. Spread is how an infection is transmitted, which may not be predictable until a novel virus is on the loose. The virus for Covid-19 is SARS CoV-2, a more lethal variant of the virus that caused the 2003 SARS outbreak. The names for a disease and its virus are not the same. Spread of SARS CoV-2 virus is hard to control because people with no detectable symptoms are carriers, and the incubation period varies. Whether animals can be carriers, and whether it will fade with warmer weather are still uncertain. However, people that have recovered become immune. Germany, and perhaps other countries, will test whether people have SARS CoV-2 antibodies in their blood – evidence of immunity. Germany is considering issuing immunity certificates to those with antibodies, releasing them from quarantine to go to work. However, survivors might still transmit the virus (based on a preliminary study from China).

A new pandemic is sparked by a mutated virus jumping from animals to humans. Animals in close confinement, especially mixes of animals, harbor an ideal stew of viruses able to spawn mutations. Some can jump to humans. That’s why many speculate that SARS CoV-2 was brewed in bats or pangolian monkeys. However, no SARS CoV-2 spark jump has been positively identified.

Epizootics and Zoonotics

The best time to stop a pandemic is before it sparks from animals. Epidemics among animals are epizootics, of concern to naturalists, veterinarians, and farmers, but few others. Epizootics are complex, affected by many variables, including biodiversity loss and globalization. Just the title of a recent paper explains it: “Changing Patterns of Emerging Zoonotic Diseases in Wildlife, Domestic Animals, and Humans Linked to Biodiversity Loss and Globalization.”

Zoonotics are disease transfers from animals to humans. Believe it or not, Zoonotics is a field of study. Its purpose is to predict, and if possible, preclude sparking of pandemics by animal-to-human transmission of novel viruses.

The leading organization coordinating zoonotics for 10 years was called Protect, initiated in 2009 “to strengthen global capacity for detection and discovery of viruses with pandemic potential that can move between animals and people.” In 2019 Protect was quietly shut down. It was run through USAID, whose mission is economic aid, and Trump officials were “uncomfortable running a cutting-edge science program” under an economic aid agency. Some elements of Protect were reassigned; for example to U Cal-Davis. However, this break-up and shuffling disrupted the global Protect scientific network at a bad time.

Pandemic planning on the National Security Council (NSC) also evaporated in chair shuffling. Funding of zoonotic disease planning by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) was not cut, as alleged in political mudslinging. Congress overrode Trump’s proposed budget cuts. However, CDC’s programs did not duplicate Protect, which flew under media radar. Confused? Pandemic preparedness is a flash point in an era of political sniping. We trust Politifact to line up the facts of this situation as well as anyone.

As widely reported by many sources, personnel vacancies at CDC, plus the exodus of pandemic preparedness staff at NSC, left the United States winging it when the Covid-19 pandemic began to unfold. No well-prepared team was set to fire up immediately. The federal government did not take a strong lead. That was left to states and localities, which has some logic. Measures appropriate to New York City are not the same as for rural Nebraska, and vice-versa. However, few state and local governments were primed for take-off either.

Lack of preparedness has inhibited most countries’ responses to Covid-19 outbreaks. Shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators have been all over the US news. Shortages seem particularly threatening in nursing homes for the elderly, who are highly vulnerable – 20% or so of infected patients die – while nursing homes have been low priority obtaining PPE, and understaffed to deal with patients in isolation.

Misinformation and Problem Solving

In any true public crisis, people dying, anybody who isn’t scared doesn’t grasp what’s going on, or thinks that they are somehow exempt from it all. Crisis generates misinformation from conspiracy theorists, opportunists, shysters, and most of the rest of us guessing, exaggerating, and just plain not understanding the situation. The old “pass the secret” party game illustrates this phenomenon. Social media accelerates the spread of misinformation, as appears to be happening with Covid-19. Wikipedia has a running summary of falsehoods, info-war propaganda, and conspiracy theories, but I’ve seen a few that Wikipedia missed.

To manage a pandemic, authorities must first keep their own heads; then supply facts, as best they can ascertain them, on which the public can rely. Facts, good, bad, and ugly, are separate from messages of hope and inspiration, like “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

We create misinformation when we do not exercise good problem-solving logic, do not understand a system, or cannot admit that “we do not know.” It’s easy to attribute a complex phenomenon, like Covid-19, to a simple cause. For example, Americans blame Chinese for Covid-19, and Chinese allege that an American biolab synthesized SARS CoV-2. If frustrated and utterly ignorant of viral spark and spread, people blame an epidemic on an angry god, “sinners,” or an “enemy” – anything simple, symbolic, and identifiable. Then they can do something simple: appease the god, punish sinners, or attack somebody. This doesn’t deter a wily novel virus, but by “doing something” people feel better (same logic as a lynch mob).

Covid-19 is only one potential calamity that our modern economy has evolved to foster. More big changes – and fast learning experiences – await. Covid-19 has temporarily driven concerns about environmental degradation out of public discussion, but these issues are still with us, and like the SARS CoV-2 virus, lurking to bite. Like Covid-19, they should be addressed sooner rather than later, but also like Covid-19, until a big bite is ripping flesh, many of us don’t take it seriously. We want to go back to our old economy, but it can’t. It’s choking on its own fumes. One small benefit of Covid-19 is that reduced activity has led to cleaner air. From that, the business world might begin to see that an economy driven by market indexes, rising GNP, and maximizing returns is not leading to a better quality of life for most of us. But don’t hold your breath.

What do we need to change? Our basic thinking about what is important to us. And we need to learn how to resolve existential crises more systemically, going for root causes and key system interventions. Conventional business logic is that technical fixes will preserve the existing system; that entrepreneurship and competition will let us “do well by doing good.” Surely the fixers will make a lot of money, create jobs, and grow the economy. However, growing just to be growing is what led to our crises to begin with.

The Compression Institute promotes different thinking to resolve problems, not specific technologies or techniques. Those may be very helpful, but only if we adopt new concepts of “success.” For anything to have lasting value, first we have to survive, and for us to survive, the natural world has to thrive with us. We too can only speculate which technologies may be viable in a new era. We will evolve them. Faced with technical issues, we are resourceful, as can be seen by grass roots initiatives to produce PPE and ventilators for the Covid-19 pandemic.

The first spark for a very different kind of economy is fully grasping that we live in a limited, finite world. A booster is to realize that our survival depends on living with nature – that we must serve it if it is to serve us. Our real reserves are nature and our ability to imaginatively coexist with it. That’s Compression Thinking. Start from what we need to do and re-invent our own economy to do it.

It is no longer radical to think that we must adopt different ideas of success – what is in the best interests of both nature and ourselves. Join our Compression Community to help unfold a direction for inventing our own new economy, from the ground up, together.

More in the next newsletter.