In the 20th century, work organizations were often described mechanically – as well-oiled machines, perhaps. Today, work organizations are more likely described biologically, like an amoeba organization, or Open Xerox. This trend should accelerate.

Old machines had rigid linkages. So do strict hierarchies, even with linkages well oiled by informal organization and electronic networks. A century ago, hierarchy was deemed the way to organize for work. By contrast, bio names suggest fluidity, more responsibility at the action level to cope with changing conditions, and quickly.

An organization is often described as “the system,” Those working in subparts of the system as “how we do things around here,” a local view. We often think of a system as just IT, but suppose we take a big view and think of our organization as a bit player in a much bigger world. For this, biological analogies are better.

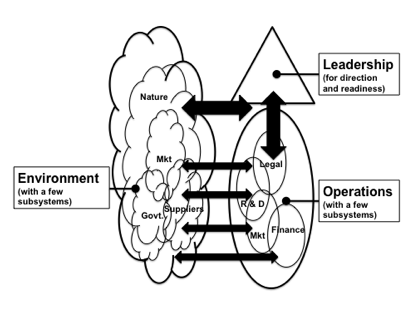

Big systems are composed of smaller systems. As is well known in physics and biology, the characteristics of a next higher-level system may be impossible to know from the behavior of the subsystems composing it because the interaction of the sub-systems form a different kind of system. Here’s a shot at describing any kind of system using just three main elements: leadership, operations, and environment:

This concept came from Slide 10 by Jon Walker. It greatly simplifies the tangled webs of reality. No one can grasp this scope of overview of a work system in which we are a tiny “subsystem,” much less the external systems that we affect. The details of all the systems in which we are embedded elude us, but just being aware of how we are a part of bigger systems including nature may be enough to blow us out of the doldrums of just doing a narrow job for the money – even if we are a CEO.

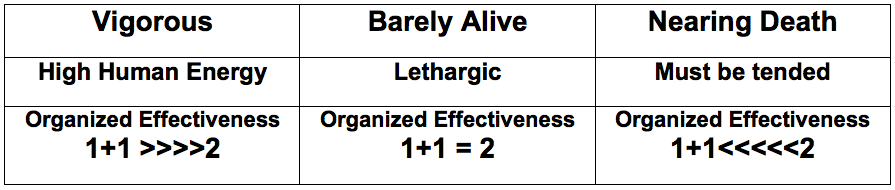

Once we describe a work organization with biological analogies, not mechanical ones, move to the next step. Question the extent to which the organization is alive and interacting with its environment. Is it vigorous, barely alive, or nearing death?

To stay alive, any biological organism has to gain energy from its environment. For many, eating and reproducing constitute most of their living activity. But to keep eating in a changing environment, they must also adapt to it. How they do that is a “leadership function,” but not exclusively. Smarter ones adapt all subparts faster. They morph if they haven’t specialized to the point of rigidity.

Humans make vastly greater use of energy that they do not eat than any other organisms. Indeed, human civilizations are built by leveraging more energy for our purposes. We also squander a great deal of external energy, some of it just for fun.

How much energy we can obtain depends on how much additional energy we can leverage from the energy expended to get it. If that yield is dropping, and it is, we have to develop more vigorous, smarter human organizations to cope with this loss of energy leverage. (Declining energy yields on fossil fuel extraction and low energy yields from alternative fuel production both point in this direction.) A vigorous learning organization has to become a network keenly sensing its total environment and interacting symbiotically with it.