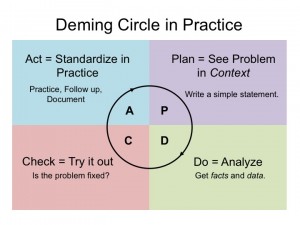

Most readers know the Deming Circle, Plan-Do-Check-Act, or PDCA, a problem solving logic that is often expressed in other formats like DMAIC or C4. Likewise, systems thinking is packaged in a variety of flavors but with a common theme of taking big-scope, multiple-viewpoint looks at problems and analyzing feedback loops.

Most readers know the Deming Circle, Plan-Do-Check-Act, or PDCA, a problem solving logic that is often expressed in other formats like DMAIC or C4. Likewise, systems thinking is packaged in a variety of flavors but with a common theme of taking big-scope, multiple-viewpoint looks at problems and analyzing feedback loops.

How they are used account for some of the differences between PDCA and systems thinking. Some organizations confine the use of PDCA to process-related problems. Others like Toyota employ PDCA when mapping corporate strategy. A deep PDCA thinker is apt to ask a lot of why questions and search for potential causal loops in the Plan stage: Are we seeing the right problem, the right way? Could our real problem be far removed from the evidence we see, perhaps a consequence of our objectives, reward systems, or preconceptions?

PDCA calls for cool heads. Detaching from emotions evoked by a problem helps us seek all the facts, but we have to condition ourselves to this discipline. Blind faith in prior assumptions guides fact seeking down blind alleys. In the entertainment field, artistry creating emotion is the objective, but if everyone unites around a common objective, agreeing on problems is possible. Then PDCA discipline may work pretty well.

Unfortunately, conflicting human objectives and emotions are the heart of many human problems. Opponents emphasize different sets of facts or interpret them from divergent viewpoints. For instance, in weighing the benefits and losses of building a new dam, those eager for its benefits see them differently from those whose homes will be flooded by rising waters. Despite these conflicts, a win/win solution may be possible unless one party’s interests include something like a sacred burial ground in the flood zone, an emotionally irreconcilable loss that makes win/win impossible.

We base many of our critical decisions, in life and in business, on core beliefs. Some we hold so axiomatically that we never voice them and can’t comprehend why others don’t share them. PDCA may help an artist improve painting techniques, but the emotional messages the artist wants to convey well up from somewhere else. And when deciding whether to marry someone, who relies on PDCA?

Unfortunately, emotional conflict fuels political strife and wars, hot and cold. Inside families – or companies – relationships may likewise be Shakespearian dramas of characters in double binds, prisoners of their own convictions, trapped in irresolvable conflicts. The comments after almost any serious news editorial reveal people locked into “positions” with no thought of how to dig for facts or how to resolve the issue.

Including behavior and beliefs in systems thinking at least attempts to deal with them as part of a total system. Systems thinking mind-map exercises may reveal to individuals not only the perspectives of others, but their own subconscious assumptions. Participants’ wealth, health, and status may be at stake. To get along, they may talk only about sports or weather, avoiding issues, but nothing ever gets resolved to manage a big, ongoing system.

All of us are drawn to fairness issues like moths to a flame. (“Not fair” is one of every child’s first phrases.) Fairness issues in many forms tempt us to ignore bigger system issues affecting us all. Overcoming our divisions to forge a common future amid difficult challenges is our biggest leadership challenge. Do that and we might be able to collaborate making a better future – doing better while using much less.