We need to question our basic educational needs. Both the quality and quantity of U.S. education are constantly under fire. District school superintendents are under pressure to do more with less funding, especially in urban areas.

Lost in the clamor is that all industrial countries have steadily ramped up both their expectations and achievements in formal education; 100 years ago only 3% of American adults were college graduates. Now it’s 30%. A college education no longer carries the same cachet, but its costs have risen 250% in constant dollars since 1980-81.

PISA scores from OECD countries regularly show American youth lagging other industrial nations. In 2009 the United States sagged to 17th down the list. Shanghai displaced Finland at the top, so educators are busy benchmarking Shanghai as well as Finland, asking what they do differently.

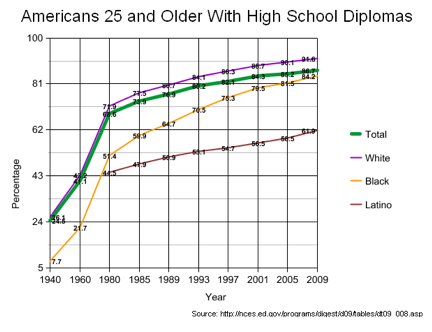

Education extends beyond a formal school experience. It’s lifelong. Some of us finish formal certificates of learning long after the system says we should. That shows up in the data on educational trends. The graph below shows them since 1940:

The non-linear scales of both years and percentages on this graph create an effect more dramatic than the slow, steady progression shown by its source data. In 1940 the percentage of adults over 25 lacking a high school education was almost 75%. Today the high school drop out rate has declined to 7% and only 11% of all adults over the age of 25 lack high school equivalent education. Of course, this creates problems. Social problems that we once might ignore now make their way into the schools. Kids are “institutionalized” longer, and upon exiting the system, can’t find work, or at least in something they like after doing time in education factories.

At the same time, employers complain that they can’t find qualified employees. In 2006 about 59% of all engineering doctorates awarded were to foreign students on a temporary visa; about half of them stay in the U.S. Then employers complain that specialized nerds can’t communicate. Initiatives to beef up STEM education proliferate. Meanwhile, K-12 teachers are urged to use technology that was science fiction 50 years ago. Some lag behind students on the latest in cool, and arguments on the proper mix of software and on-line communication versus live contact for education continue.

So what gives – besides too many variables in the soup? We can’t agree on the basic objectives of formal education, much less on what ingredients are missing from the soup, or how to re-mix those already in it.

Projecting the exact skills we will need 10-20-30 years hence is impossible. While education includes skills training, more importantly it should groom all students to be fast learners, and from studying reality, not internet and multiple choice exams. That part of education takes place away from a classroom, and it is ongoing. Companies should regard this kind of education on the job as an investment, not a cost to minimize – or externalize. An organization of collaborative fast learners beats cubicle functionaries.